Displaying items by tag: emilie du chatelet, voltaire, emilie & voltaire opera, nicholas gentile, opera, opera australia

Émilie du Châtelet 1738 - Episode 2

Nicholas Gentile and I have written an opera about Émilie and Voltaire and were invited to speak about it to Sydney's Queen's Club. Episode 1 of the speech shows Émilie as a girl being shown off by her fond father as a prodigy in mathematics and natural science. She also, with the approbation of her mother, excelled at playing the harpsichord.

'In a corner is a tall, lean young man who looks rather bemused by this precocious eight-year-old. Finally he steps forward when the company are speculating about the possibility of life on other planets. He gives Émilie a teasing smile and says, "Mademoiselle, could there be human beings on Mercury? Reflect: if they do live there, they’re twice as close to the sun as we are, so their brains must surely be fried. The sun is nine times bigger for them than it is for us—what does that do to their idea of the universe? Could anyone in that situation think like us at all?"

'She replies, "I have no opinion, monsieur; I’m here on earth. But if there are sentient creatures on Mercury, why should they be human? All we can guess is that they accord with the infinite diversity of nature."

'The silenced young man is Voltaire, a successful dramatist and poet, a keen philosopher and writer, and a huge asset in aristocratic society. He’s not an aristocrat himself, however. He was born François-Marie Arouet in Paris, near the law courts and Notre-Dame. He was educated at an excellent Jesuit college where he mixed with the sons of noblemen, dazzled his teachers with his intellect and wit, and wrote the school play at the end of each year. When he went into society he fitted in by making up a noble name for himself—"de Voltaire"—and forming liaisons with actresses or duchesses, and no one in between.'

My first film review

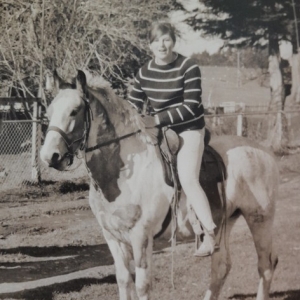

The picture was taken in the country near Gisborne, New Zealand, in the sixties. I mean, it’s so tell-tale: when else would a teenager on holiday sweep her hair up and choose white jeans to ride a horse? This was at the end of my last year at school, a period in which I kept the one and only diary of my life, which lasted until November 1966.

Rediscovering the diary, I came across what I realise is my first film review. It is interesting (at least to me, now I’m writing screenplays) to note that it isn’t a fan rave about Peter O’Toole (though I adored him, particularly for his Henry II opposite Richard Burton’s Becket) but a writer’s assessment of how the film is put together. Here it is verbatim, with all its sins upon its head.

‘Today I went with Sue Flanigan to Lord Jim. Starring Peter O’Toole. In this I missed a real speech, too many incoherent half-sentences. True, Jim was not talkative in the book. Too coiled up inside. The real flow of the narrative, picturesque, arresting, penetrating, came from Marlow in the book. In the film a Jack Hawkins Marlow gave a few conventional, regretful remarks and left Jim to his tortured silence. Unfortunate, the film desperately needed Marlow. Even a direct clash with hostile forces and a dramatic rescue soon after Jim’s arrival failed to speed up the action before Jim’s seizure of power in Patusam. Either the film script needed a Marlow or the plot must be thickened. Richard Brooks did neither. He was happy to tamper by removing but not by addition. He retained some hideously difficult scenes (to act, I mean) and shifted characters so that the scene could be filled with more than just a man and his thoughts in many parts. Brooks retained quite well the theme of Tuan Jim. It was simple enough anyhow. Simplicity was perhaps the difficulty. After all, Conrad originally intended it to be a short story, didn’t he? It widened into a deeper personal narrative and almost a dissertation on men and the fantastic complications which their sense of ‘honour’ can achieve in their lives. Much of it, let’s face it, is padding. A seaman’s yarn, with deep and engrossing stories all thrown in, almost as asides. Jim’s love of the girl. Dain Waris. Stein. Although Stein and the villain are necessary figures. The book rambles unashamedly but the reader has the chance to glance back and pick up the thread of the theme, reread the final conversations with the villain of the piece (excuse the music-hall bit but what was the man’s name—Brown?). The book triumphantly emerges as a whole.

‘The film was slow. It had to be because there was no Marlow to weave a texture of words over the bare thread of the action. The padding, the relationships between Jim and the others proved unattainable in a film if used in Conrad’s original form. There were relationships not of action but of feeling. They were irrepressible, particularly by Jim.

‘Perhaps Peter O’Toole did play Jim as a “neurotic bore”. If so it was not his fault. Or Joseph Conrad’s. The whole idea should have been scrapped in the first place. Lord Jim is simply not a film. It’s not spectacular enough to pass off as a "great epic" and earn millions by catering to vulgarity. It needs sensitivity and a sort of 6-dimensional approach, a panorama of emotion and exposition, I don’t know, and I suppose you couldn’t have Marlow droning away – genius or a new medium to put it anywhere except on the pages of Conrad’s book. Therefore it’s not an "art" film either. It’s an irritating middling.’

Dear reader, was I dreaming already of Émilie & Voltaire in my desire for six filmic dimensions? It could be said our streamed cinematic opera will provide them. Emotion: Nicholas Gentile's divine music, the jealous lovers, the passionate lyrics. Exposition: the authentic setting of Cirey in France, a true historic discovery, a woman’s groundbreaking contribution to science.